Written by Bronwyn Bocher, Head of History (High School)

As a recovering procrastinator, I am in the habit of reflecting on the reason behind why I may be putting off a particular task. I think in the case of writing this particular piece, on my experience participating in the Gandel Foundation Holocaust Education program, the reason was because I didn’t have the vocabulary to fully express the seismic impact those eight days in Melbourne had on me. So, I’ll start with something easy. The context: Late in Term 4 of 2024, I was offered the opportunity to join this year’s Gandel Foundation Holocaust Education program. I was to join the 2023 cohort, who represented educators from around Australia who had gone through a rigorous selection process and who had been bound for a three-week program hosted at Yad Vashem in Israel. But then October 7th happened.

In the months of devastation and uncertainty that followed, the team at the Gandel Foundation and Yad Vashem showed resilience and agility in reconceptualising the entire program to rather take place in Melbourne during the summer holidays in January of this year. Needless to say, in the first few days, I felt like a real noch schlepper, or perhaps an imposter, who didn’t have to go through the rigorous selection process but serendipitously found myself part of a cohort of 21 Australian educators and members of education adjacent industries. This cohort reflected the broad spectrum of schools across Australia. Three of us were from Jewish schools (myself from Sydney and two from Melbourne). I mention this as a significant point because Jewish schools are not usually included in the program, as the intention of the scholarship, established by John and Pauline Gandel, is to give access to Australian teachers the opportunity to learn about teaching the Holocaust from experts at Yad Vashem. An opportunity that defies the usual offering of professional development. We were luckily included this year, though (and hopefully in the years to come), which seemed very timely and allowed for rich and interesting contrast into Holocaust education within Jewish schools. Most Jewish people struggle to remember exactly when they first heard about or learned of the Holocaust—for many of us, it is part of the fabric of our collective memory.

Over the course of eight days in early January we collectively contemplated some of the most challenging questions around Holocaust and historical pedagogy: How can we understand the unimaginable? How can we teach the traumatic in a safe way that doesn’t traumatise? What can we learn from the choiceless choices of those who experienced the Holocaust?

Yad Vashem offers some guidance to these, anchored in a steadfast ethos that is committed to teaching the Holocaust. A key principle is “safely in; safely out”. Our students need to be carefully guided in their study to understand the rich lives of Jews prior to the atrocities that tore through Europe in the 1930s and 1940s. Once the threshold into the unimaginable events of the Shoah is crossed, the focus shifted even more so to individual testimonies and stories explored through primary sources. And finally, the return to life after the indescribable.

Besides the rich array of resources I relished exploring and bookmarking for future use and to share with Moriah teachers, my biggest takeaway from the whole experience has been far more intangible and existential.

On Wednesday, 8 January, the third day of the program, we had a special day on antisemitism. While this is a concept obviously imperative to understanding the Holocaust, it is, unfortunately, also a living concept in our lives today. Over the course of the day, we heard from experts on the history and morphing of antisemitism over time; we gained shocking statistical insight into the growing problem of antisemitism in Australia and heard of the advocacy efforts of Jillian Segal, Australia’s first Special Envoy to Combat Antisemitism, and Alex Ryvchin, Co-CEO of the ECAJ. While confronting, these are topics not unfamiliar to a Jew living in Australia in 2025. It is easy to feel angry, scared and a deep sense of grief.

What I wasn’t expecting to experience, was hope. This was largely derived from the non-Jewish Gandel graduates who asked “what can we do?”, “how can we help?”. As well as their constant thread of commitment and passion to teaching the Holocaust. Their assertion, after listening to the stories of two survivors, that they would, as Elie Wiesel suggested, “become a witness” themselves. The realisation that each of these amazing individuals would go on to impact thousands of students, like a great and growing ripple, brings a lump to my throat. They gave voice to the silent majority in Australia, those who find these antisemitic attitudes and attacks abhorrent, but whose silence has been exceptionally painful to the Australian Jewish community. I will always be grateful for the immense trust and empathy that our cohort built in just over a week, so deftly guided by Yael Eaglestein, Sarah Levy, and Yohai Cohen of Yad Vashem.

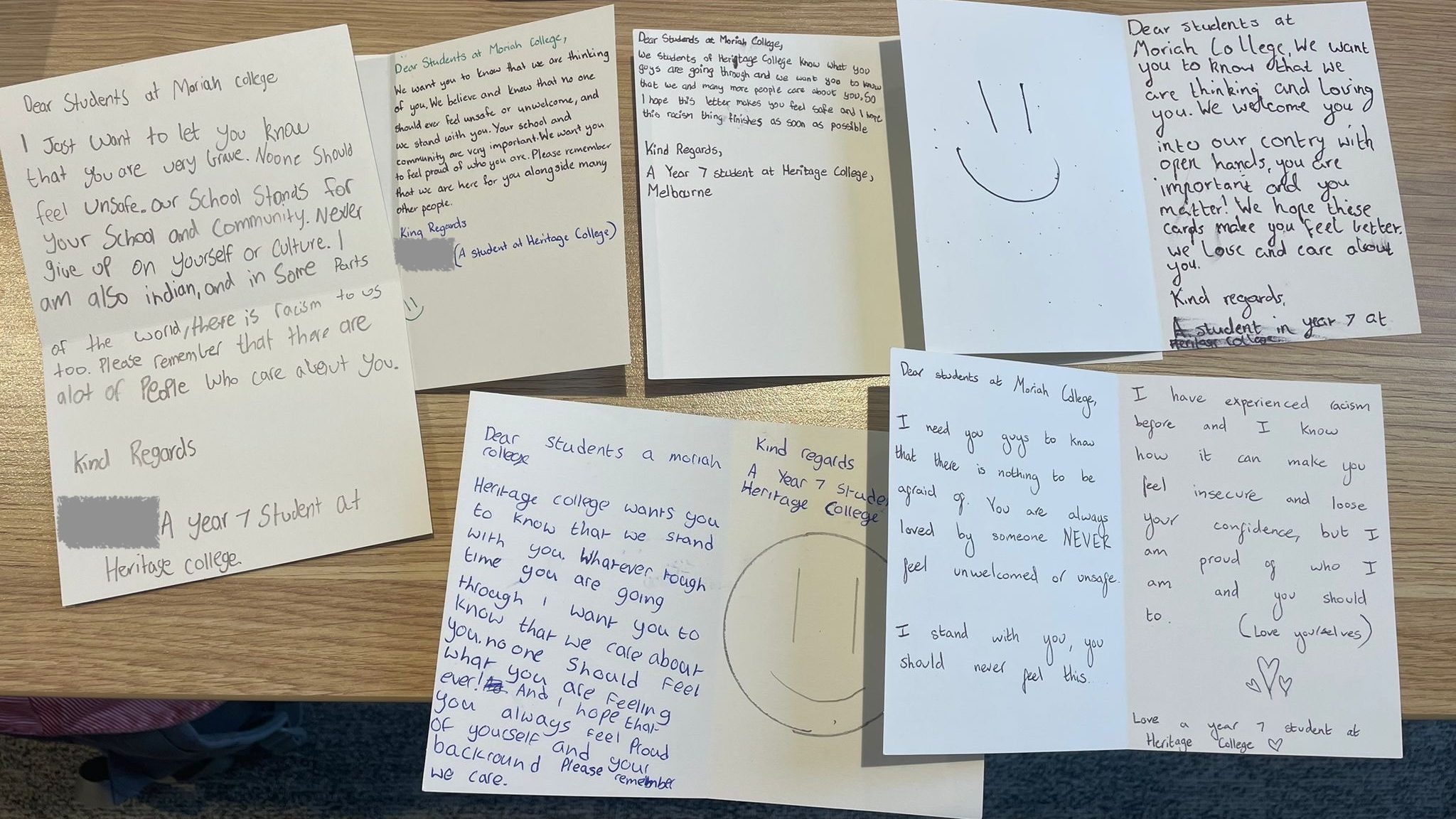

Beyond my wildest expectations, the impact this program had on each of us was made evident, when one of my fellow Gandel graduates, having started the new school year, reached out to share that her students at Heritage College in Melbourne, having been so moved and inspired by her teaching of the Holocaust and discussions of the antisemitic attacks around Australia, that they wanted to write cards to students at Jewish schools. I’ve lost count of the number of times I have read over the sample of her students’ cards she sent a picture of.

This is the power of education.

This is the power of a teacher.

This is the power of studying History.

These powerful messages of solidarity and empathy are currently on their way to Moriah College, where we will share them with our students, staff and community.

Once we have poured over them and found hope, comfort, and strength from them, they will find a place of honour on display in our school. They will serve as a reminder for all, that History can teach us so much more than just the past.