Introduction

There has been considerable debate about the foreshadowed plan by the Government of Israel to announce the unilateral “annexation,” of, or “extension of sovereignty” (הרחבת ריבונות) over, or application of Israeli civilian law to, parts of Judea and Samaria (also known as the West Bank). It is important to note at the outset however, that: no plan has been announced; no final annexation map has been presented; no vote has been taken; and the US Government, which (under article 28 of the Government’s Coalition agreement) must consent, has not done so. In short, we do not know if annexation will proceed, when, and in respect of what area(s), or with what consequences for the people who live in the areas concerned.

The issues surrounding annexation are both complex and regarded by many as controversial, much more so than, for example, the 2018 decision by the US Government and some others countries including Australia, to recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

There is a diversity of viewpoints about these matters within diaspora Jewish communities as there is within Israel, but it is important for the discussion to proceed on an informed basis, and that is one of the purposes of this paper. It is for these reasons that this article has to be reasonably detailed and accordingly longer than otherwise might have been the case.

What is Annexation?

Currently no country has recognised sovereign rights over any of the West Bank and therefore, in strict legal terms, the area cannot be annexed in the sense of one country seizing the land of another. While Israel already exercises military and limited civil control of the area, it has never sought to assert its sovereignty over the area.

However, it is possible for Israel to extend its sovereignty, or to apply Israeli civilian rule, to some or all of the area and to do so either by agreement with the Palestinians in accordance with the Oslo Accords, or without any such agreement, regardless of the contested legality of any such move, as it now proposes.

A unilateral act of this kind, which seeks to change the status of the West Bank, appears to be contrary to the Oslo Accords, which continues to bind Israel and the Palestinians equally. There are also customary International law rules, which may have implications on recognition of such a change in status.

It should be noted that the Oslo Accords (initially signed in 1993) have a complex legacy. They raised expectations of a final peace agreement and an end to the conflict, which culminated in Palestinian rejections of wide-reaching internationally brokered offers that could have produced a viable two-State outcome. The breakdown of final status negotiations in 2000 ushered in one of the bloodiest periods in Israeli history, the Second Intifada. At the same time, the Oslo Accords also led to unprecedented mutual recognition and cooperation between Israel and the Palestinians, which are necessary preconditions to any lasting peace. While the Palestinians regularly threaten or purport to disavow or terminate the Accords, presently they remain in effect. Unilaterally changing the status of disputed territories would violate the terms of the Oslo Accords and could therefore harm Israel’s standing internationally and, depending on the extent and the terms of annexation, for reasons canvassed later in this paper, may call into question the Zionist vision of Israel as a Jewish and democratic State.

What is the West Bank?

The West Bank is land on the west bank of the Jordan river, occupied by Israel during the defensive war of 1967 (the Six-Day War), but never (with the exception of East Jerusalem) incorporated within Israel proper. It was once the heartland of Biblical Israel (Yehuda and Shomron). In more recent times, Jewish communities had existed in areas like Hebron and what is now Gush Etzion until they were brutally driven from these areas in the 20th century.

Prior to World War 1 the West Bank was part of the Ottoman Empire. After that war and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the area (from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea along with the large territory on the east bank of the River known as Transjordan), was controlled by Great Britain. In 1923, Britain became mandatory (or custodian) of the land under the League of Nations British Mandate of Palestine, which called for the creation of a Jewish national home in Mandate territory. Also in 1923, an independent Arab state of Transjordan (later the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan) was declared in the parts of Palestine east of the Jordan River. In 1948, Britain relinquished control of the remaining part of the British Mandate for Palestine, immediately prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. In 1949, following Jordan’s invasion of Israel, Jordan occupied the West Bank and annexed it in 1950.

Key dates and Events:

- On November 29, 1947 – the UN (Resolution 181) approved the partition of British Mandate Palestine into two states for two peoples – Jews and Arabs. This proposal was accepted by Israel but violently opposed by the Arab world resulting in an invasion of Israel.

- Israel’s War of Independence ended in 1949 with armistice lines (the Green Line) defined by the facts on the ground. These “lines” (which were expressly stated in the Armistice Agreements not to be borders) lasted 18 years, until replaced as a result of Israel’s resounding victory in the 1967 Six-Day War. In the period between 1949-1967 there was ongoing opposition to the very existence of Israel and demands to permit Palestinians who fled what became Israel, or were displaced during the war to return to Israel. Israel justifiably resisted this openly stated attempt to reconstitute Israel as an Arab state. However, there was no attempt to create a Palestinian state and there was no international call to do so. The West Bank (including east Jerusalem) was directly annexed to Jordan. Gaza was placed under Egyptian military administration.

- In 1967, immediately following the end of the Six-Day War, Jerusalem was united under Israeli jurisdiction and in 1980, the Jerusalem Law was passed by the Knesset, regulating the status of united Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

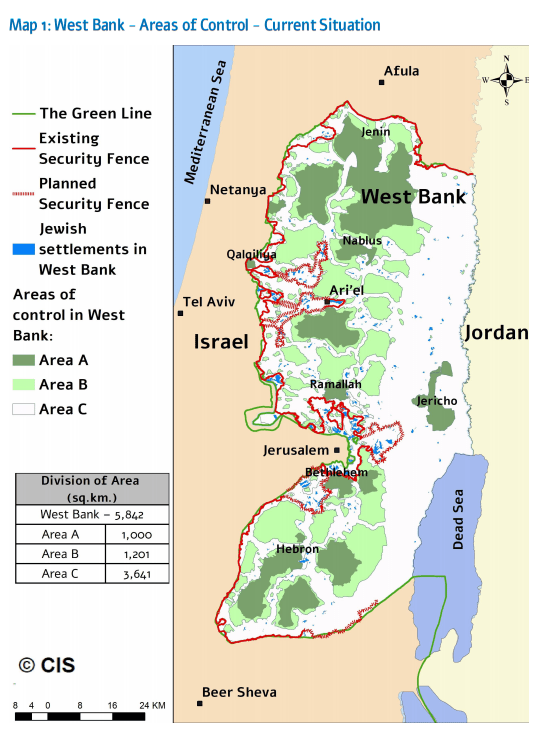

- Years of continued Jewish settlement in the West Bank and the signing in 1993 of the first of the Oslo Accords, led to the 1995 Interim Agreement, which demarked and defined the interwoven Palestinian and Jewish areas in the West Bank, as Areas A, B and C:

Area A – now comprises about 18% of the West Bank, with the Palestinian Authority (PA) exercising full civil and security control. Area A includes eight Palestinian cities and their surrounding areas including Nablus, Ramallah, Bethlehem, Jericho and 80 percent of Hebron (H1), with no Israeli settlements. Entry into this area is forbidden to all Israeli citizens.

Area B – now comprises about 22% of the West Bank with PA civil control and joint Israeli-PA security control.

Area C – comprises areas of the West Bank outside of Areas A and B, including 20% of Hebron (H2), settlements (blue dots on the map below), outposts and declared “state land”, with full Israeli civil and security control.

Demographics of the West Bank

- The total population of the West Bank is currently estimated at around 3 million (excluding East Jerusalem).

- 420,000 – 450,000 Jews, live almost entirely in Area C, including in about 130 settlements of various sizes as well as in more than 100 outposts, which are unrecognised by the Israeli government.

- About 200,000 of the Jewish settlers are concentrated in four towns situated just beyond the Green Line: Modi’in Illit, Beitar Illit, Ma’ale Adumim and Ariel.

- Estimates of the Palestinian population in Area C, vary between 100,000 and 200,000.

The Trump Peace Plan

In January 2020, President Trump’s “Vision for Peace” was unveiled with a ‘conceptual map’ (see below) “designed to demonstrate the feasibility for a redrawing of boundaries in the spirit of UNSCR 242, and in a manner that” achieves nine key objectives, including:

- satisfaction of the security requirements of the State of Israel;

- establishment of a Palestinian state;

- acknowledgement of the State of Israel’s valid legal and historical claims; and

- avoidance of forced population transfers of either Arabs or Jews.

The full version of the “Vision for Peace” can be viewed here https://www.whitehouse.gov/peacetoprosperity/

The “Vision for Peace” states, amongst other things:

- “It is essential that this Vision be assessed holistically. This Vision presents a package of compromises that both sides should consider, in order to move forward and pursue a better future that will benefit both of them and others in the region”.

- “This Vision aims to achieve mutual recognition of the State of Israel as the nation state of the Jewish people, and the State of Palestine as the nation-state of the Palestinian people, in each case with equal civil rights for all citizens within each state”.

- “The peace agreement that will hopefully be negotiated on the basis of this Vision should be implemented through legally binding contracts and agreements.

- “This Vision creates a realistic Two-State solution in which a secure and prosperous State of Palestine is living peacefully alongside a secure and prosperous State of Israel in a secure and prosperous region”.

Under the “Vision for Peace,” Israeli sovereignty over 30% of the West Bank is linked to Palestinian statehood by requiring any annexation measures to be effected within a four-year process that would lead to a two-state resolution to the conflict, with a Palestinians state on 70% of the West Bank. The “deal of the century” requires Israel to accept this premise in exchange for US support for sovereignty and if it does it can annex territory before the end of the four-year process.

Following publication of the “Vision for Peace”, Prime Minister Netanyahu announced that he would apply sovereignty based on that plan, which allowed Israel to annex up to the 30% of the West Bank. He also committed to only proceeding with annexation with US approval. The US has not yet given the green light to any annexation. Nor has the joint Israeli-US mapping committee set the exact contours of any area to be annexed.

The Israeli Position

The discussion about annexation occurs not only in the context of the Trump administration’s “Vision for Peace” proposals, but critically, a history of PA rejection of Israeli and other peace proposals and the overwhelming frustration with the Palestinian leadership’s unremitting failure to accept Israel’s right to exist as the nation state of the Jewish people, a position they maintain even 72 years after the establishment of the State of Israel, following the UN’s endorsement of the principle of two states for two peoples, and 53 years after the Six-Day War.

The Prime Minister and others in the Government, have stated that the government intends to unilaterally annex or assert sovereignty over, settlements (whether some or all is not known) and/or the Jordan Valley with a possible announcement in that regard on or after 1 July 2020.

As yet, there is no clarity as to whether, or if so, in respect of what area(s) or settlements, annexation might occur, or when. The position of the Blue and White party on the issue is neither clear nor unanimous.

Opinion polls in Israel reflect the diversity of views within Israeli society on this issue.

Sections of Israeli society including the settlers, maintain that Israel has historical rights to that area, biblical and under International law including because it was acquired in a defensive war in 1967. Others argue that annexation will prevent the establishment of a viable Palestinian state and thus spell the end of a two state solution and/or create an unjust system if Palestinians living in the annexed areas are not offered a path to Israeli citizenship.

Security is justifiably a paramount concern for Israelis. The West Bank has twice been used by neighbouring states as a base for launching armed attacks against Israel, and as a base for terrorist operations against Israeli civilians. Nothing must be done that would weaken Israel’s ability to protect its population and territory. An Israeli security presence in the Jordan Valley to prevent the flow of arms and fighters into a future Palestinian state or into Israel, is entirely justified and Israel itself has made proposals for its security concerns to be addressed, including in respect of the Jordan Valley, without necessitating the Jordan Valley formally becoming part of the sovereign territory of Israel.

The failure to reach agreement thus far does not rule out an agreement in the future. Attitudes and circumstances change, however slowly. It is not uncommon for conflicts to play out over long periods.

The Palestinian Position

The PA is opposed to any form of “annexation”. This is unsurprising given:

- the absence of peace and the absence of a two-state resolution of the conflict is fundamentally the result of the rejection by the Palestinian leadership of the legitimacy of the State of Israel as the national home of the Jewish people;

- the rejection by Palestinian leadership of serious, internationally supported peace offers by Israel, including those made in 2000, 2001 and 2008, which would have produced a viable two-state outcome;

- a resolution of the conflict has been further undermined by Palestinian leaders taking unilateral steps, including a declaration of Palestinian statehood, to try to change the status of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, in violation of legally binding agreements;

- the PA has rejected any opportunity for negotiations at least since 2014 and significantly, has rejected the Trump Administration’s Vision.

- perhaps most amazingly, the PA rejected the Olmert Peach Plan, which offered a realistic two-state solution involving a territorially-contiguous Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza, involving land swaps to fully compensate for the settlement areas to be incorporated into Israel as show in the map below.

Given this reality, it is reasonable for both the US Administration and Israel to try a new approach to send a signal to the PA that refusal to negotiate may be costly to Palestinian interests, and that the Palestinian belief that “time is on their side” is mistaken.

The Palestinians have little ability to influence the course of events leading to annexation. However, they could:

- attempt to garner international support, perhaps even generate tangible measures against Israel, such as sanctions;

- declare Palestinian independence in pre-1967 borders with east Jerusalem as its capital and seek international recognition;

- totally suspend security coordination with Israel;

- scuttle the PA leaving a dangerous void at Israel’s doorstep; and

- Hamas can be expected to seek to widen its influence in the West Bank and may attempt to ignite the Gaza front (with the Islamic Jihad).

Any proposal to apply Israeli sovereignty unilaterally over the Jordan Valley and/or the settlements, even if limited to the major settlement blocks contiguous with the Green Line, is highly unlikely to force a change of attitude by the Palestinians, or end the conflict, or terminate Palestinian claims.

However the PA’s attitude may be changing if a recent report in the French wire service AFP is accurate. AFP reported that the PA sent a proposal to the international peacemaking Quartet on the Middle East (the US, Russia, EU, and UN), saying that it is, “ready to resume direct bilateral negotiations where they stopped,” in 2014. That would be a most welcome outcome, but it may be inaccurate or turn out to be a false dawn.

The US Position

President Trump’s Vision for Peace appears to be the catalyst for the current annexation initiative.

The plan was conceived as a “package deal” allowing for the annexation of 30% of the West Bank, and subsequently paving the way for the establishment of a Palestinian state in the remaining territory.

Given its own political considerations, it is unclear whether the US will accept unilateral annexation as opposed to the Vision for Peace proposals. There is also concern in the White House that such a move could endanger relations with moderate Arab states, and ongoing efforts to counter the Iranian threat.

International Reaction

The vast majority of the international community is opposed to annexation, including the PA, Israel’s Arab neighbours, and the gulf states (with whom much progress in improving bilateral relations has recently been made) and most other nations, as well as international entities such as the UN and the European Union.

The Australian Government, traditionally one of the few that can be relied upon to support Israel internationally, on 1 July 2020 issued a statement in which the Foreign Minister “urged all parties to refrain from actions that diminish the prospects for a negotiated two-state solution, including…land appropriations, demolitions and settlement activity.” The statement noted that the Government was “following with concern possible moves towards the unilateral annexation or change in status of territory on the West Bank” and that “Australia has raised our concerns with Israel in relation to indications of annexation…”

The thrust of the international concern is that Israel does not have the right to unilaterally change its borders. Indeed Israel itself has complained bitterly in the past about proposed Palestinian unilateral action such as the attempt to change the status of the West Bank by the unilateral declaration of a Palestinian State, in violation of legally-binding agreements. The legal obligation not to act unilaterally, that is by taking initiatives other than by agreement between the direct parties, to try to change the status of the West Bank, applies equally to Israel.

Clearly, the nature and extent of the adverse reaction to annexation will vary, depending on the extent of annexation and the terms applying to it.

Annexation Options

Annexation could take several forms, for example:

- a symbolic gesture – e.g. annexation of Ma’ale Adumim (effectively a Jerusalem suburban settlement), only;

- Annexation of certain settlements (comprising 3% of the West Bank);

- Annexation of the main settlement blocks (comprising 10% of the West Bank);

- Annexation of the Jordan Valley (comprising 17% of the West Bank);

- The full Vision for Peace annexation (comprising 30% of the West Bank).

A Jewish Diaspora Perspective

We have been especially blessed and privileged to have witnessed in our lifetime the truly miraculous realisation of the Zionist vision – a Jewish and democratic State in Eretz Yisrael.

We dare not take it for granted and we must not do anything to imperil Israel or the Zionist vision.

Whilst Israel’s policies and actions are a matter for her citizens whose lives and safety are at stake and for their democratically elected government, Diaspora Jewry also has ‘skin in the game’ and the right to express views and be heard.

Further, depending on the details, diaspora communities may be affected by annexation, for example, if the measures that are announced:

- weaken support from among Israel’s most proven and durable allies, such as Australia, and political moderates who have been sympathetic to Israel;

- counteract the efforts of diaspora communities to maintain wide public and bipartisan political support for the State of Israel, which is central to our interests and ethos as both Australian Jews and Zionists; or

- weaken the attachment to Israel of some sections of Jewish youth whose commitment is already being tested in the challenging, fake news, cancel culture and woke times we live in.

Each of these affects would constitute a heavy price to pay for a decision that it has been argued by Robert Satloff, Executive Director of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, “would impose impossibly high costs and deliver few benefits” https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/im-an-ardent-zionist-but-israels-annexation-makes-no-sense/2020/06/25/f949e6a4-b59e-11ea-a8da-693df3d7674a_story.html

Conclusion

The future of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state is critical and ought to guide our views on the issue of annexation, such that any extension of sovereignty must not:

- compromise Israel’s fundamental Jewish and democratic character;

- deprive the Palestinians living in areas under direct Israeli civilian law of full citizenship and equal civil and religious rights;

- prevent the realisation of a genuine and realistic two-state solution or render unviable the establishment of a demilitarised territorially-contiguous Palestinian State at some point in the future, thereby foreclosing on the possibility of a two state outcome. This would lay the foundations for a bi-national or unitary state, which would mean the end of Israel as a Jewish State.

About the Author

Robert Goot AO SC is Chairman of the Trustees and a Life Patron of Moriah College, the Co-chair of the Policy Council of the World Jewish Congress and a past President and current Deputy President of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry.

The views expressed in this article are his own

and not necessarily the views of any organisation with which he is associated, nor the staff and pupils of

Moriah College.